The Money Chase

Moving from Big Money Dominance in the 2014 Midterms to a Small Donor Democrcay

Five years after the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United v. FEC decision, what are the roles of large donors and average voters in selecting and supporting candidates for Congress? This report examines the role of money in the 2014 congressional elections from both quantitative and qualitative perspectives, and demonstrates how matching small political contributions with limited public funds can change the campaign landscape for grassroots candidates.

Downloads

Arizona PIRG

Five years after the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United v. FEC decision, what are the roles of large donors and average voters in selecting and supporting candidates for Congress? This report examines the role of money in the 2014 congressional elections from both quantitative and qualitative perspectives, and demonstrates how matching small political contributions with limited public funds can change the campaign landscape for grassroots candidates.

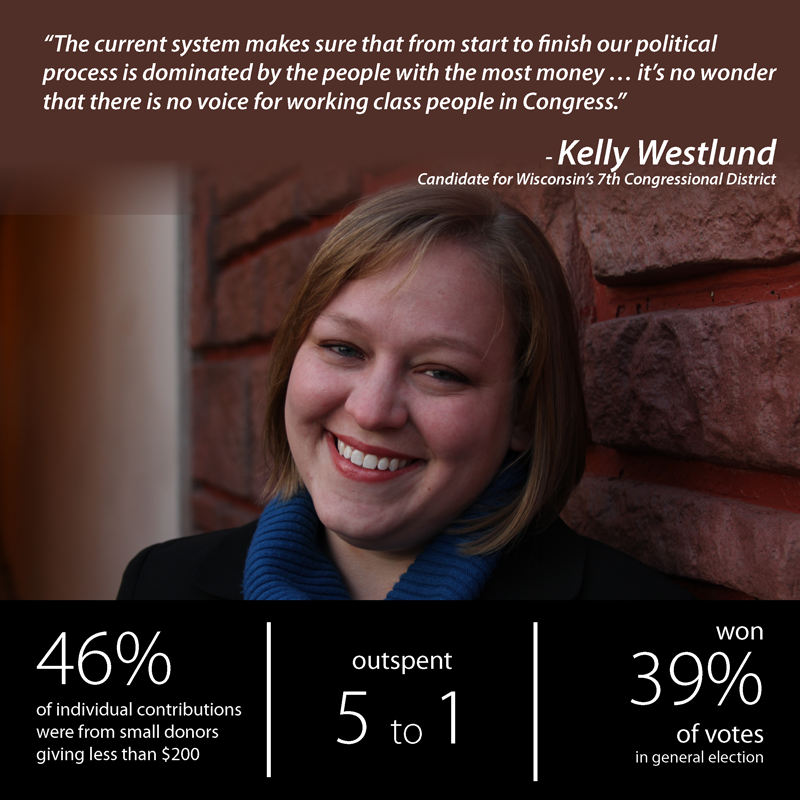

To her first run for Congress, Kelly Westlund brought experience as an Ashland City Councilmember, executive director of the Alliance for Sustainability and as a small business owner.

As a local elected official, Westlund saw how decisions made in other places affected her community, and when she looked at their current Representative, Sean Duffy, she thought she could do better and decided to run against him.

Westlund says, “Most of my network is waitresses and teachers and firefighters and police officers. I don’t have a network of millionaires and billionaires that I can call… I knew the system was broken but it was so much worse than I could have imagined.”

Amanda Renteria worked as a financial analyst for Goldman Sachs and attended Harvard Business School, but she ultimately decided to shift her career path to working in government to help others. She went on to work for Senator Debbie Stabenow and became the first Latina Chief of Staff in the history of the Senate.

She said, “What’s tough is when you see powerful forces win and people aren’t better for it…Three of the poorest cities [in the nation] happen to be here in Central Valley, yet we have the largest farm revenues. You look at it and say, ‘who’s representing these folks?’ and ‘how do you make sure the influence is fair, that everyone has a voice?’ If there is only a one sided debate in any political argument, people really aren’t getting the full picture of potential leadership.”

A decorated former Marine Colonel in a district with a high concentration of veterans, David A. Smith felt that veterans were underrepresented in Congress and the VA needed fixing, so he decided to throw his hat into the ring.

Smith saw that incumbency provided a significant advantage in the money race: “The money that incumbents can bring in is virtually limitless,” according to Smith. “Any incumbent, by the sheer fact they’re incumbent, they can raise as much as they want. I think it’s literally a blank check.”

Reflecting on the campaign’s lessons, Smith says that “one thing that I learned is how few people had ever given to a political campaign, even folks who will talk your ear off about politics. The other thing is how many people live paycheck to paycheck, and just don’t have the money.”

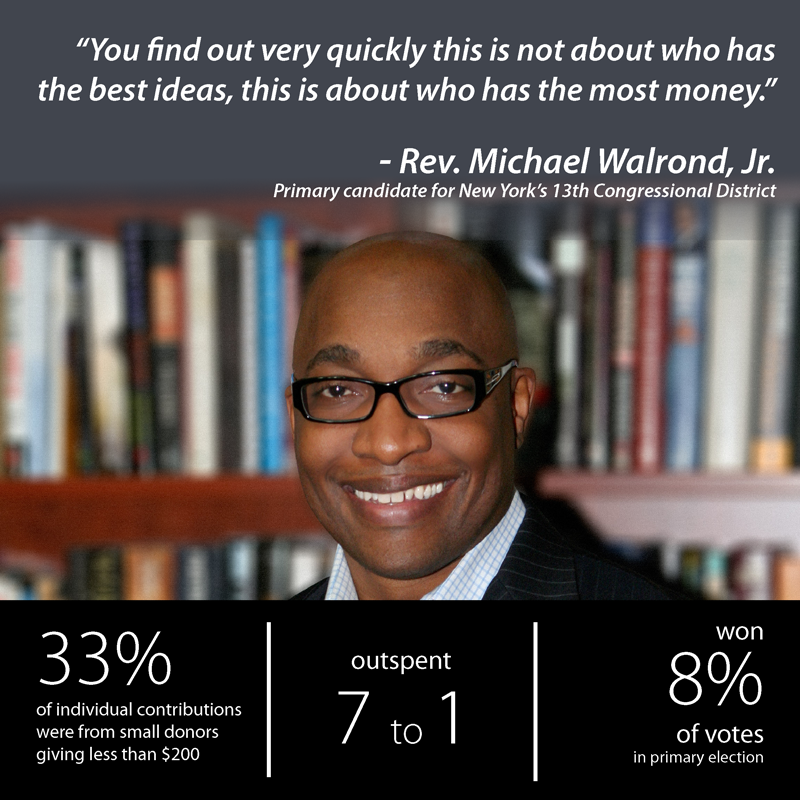

Rev. Michael Walrond Jr., locally known as Pastor Mike, leads a congregation in Harlem committed to social justice.

From serving his community as a pastor for ten years, Walrond heard “a tremendous amount of frustration with elected officials” and he threw his hat in the ring to show you don’t need to wait for permission from the political insiders if you have a passion to make a change. Yet he saw how big money shaped his ability to run an effective campaign and get his message out.

Walrond says, “When I would go to candidate endorsement interviews, before anybody asked me what I believe on immigration, what I believe about education, what I believe about criminal justice reform, the first question was how much money have you raised and how much money can you raise.”

Key Findings

•Candidates for the U.S. Senate must raise an average of $3,300 every day for six years to match the contributions collected by median 2014 winner; House candidates must raise $1,800 every day of their two-year cycle.

•Relying exclusively on small donors, Senate candidates would have to secure at least 17 contributions every day and House candidates at least nine in order to keep up.

•In 25 targeted 2014 congressional races, successful candidates and their closest competitors received more than 86 percent of the funds they raised from individuals in contributions totaling $200 or more.

• Only two of 50 candidates in these competitive races raised less than 70 percent of their individual funds from large donors, while seven relied on big donors for more than 95 percent of their individual contributions.

•This big money system filters out qualified, credible candidates who lack access to large donors. Four of these candidates are profiled in the pages below.

•Kelly Westlund, lost WI-7 general election: “The current system makes sure that from start to finish our political process is dominated by the people with the most money…it’s no wonder that there is no voice for working class people in Congress.”

•Rev. Michael Walrond, lost NY-13 Democratic primary: “You find out very quickly this is not about who has the best ideas; this is about who has the most money.”

•David A. Smith, lost FL-7 Republican primary: “It’s very difficult for a first-time candidate, unless you’re personally prepared to write a big check to break into it.”

•Amanda Renteria, lost CA-21 general election: “Given my network, where I come from, where I’m running, I expected that I wasn’t going to have huge donors. You have to ask folks for help that have been in your network and that understand where you’re running and why it’s important. That for me ended up being a small donor base.”

•A federal program matching small contributions with limited public funds would have helped the profiled candidates compete more effectively against their big money-backed opponents by substantially narrowing the fundraising gap. One candidate would have raised significantly more money than her opponent if a matching fund program were available. The other three candidates would have narrowed the fundraising gap by an average of more than 40 percentage points. More importantly, they would have had significantly more resources to get their messages out and hit the minimum threshold for running a competitive campaign. And, they would have been able to do so raising two or three small contributions each day as opposed to the nine or more they currently need to keep up.